|

Learning,

a Lifelong Endeavor

S. I. Inc. has always

been in the business of educating its clients. This took the form of classroom instruction

when we were marketing MCS-3. When

developing a capability for a client, like the CRM system for a systems

integrator, we always build into our contract time to teach the users of the

product how to get the most from our work.

Early in his career When we are not doing the

work, or teaching others, we are educating ourselves. This means taking courses or just plain

reading books and trying things out.

Some of our best products and services came from learning about

something, testing the ideas, and developing a capability to offer this to

our clients. We are not afraid of

taking a three inch book off the shelf, opening it to page one, and reading

it complete to the end. In fact, there

is money to be made in learning how to do something that way, and selling the

instruction to a client. There is a cute story

told about the late Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter, although I do

not know if it is true. The old man

was lying on his death bed reading a book when a visitor came into the

room. The man said: “Felix, what are

you reading?” To which the Justice

replied: “This is a Greek Grammar and I am teaching myself Greek.” The man, taken aback asked: “Why are you

doing that?” “Because I do not yet

know Greek” shot back Frankfurter! Live as if you were to

die tomorrow. Learn as if you were to live forever. High

Tide Software Taps S. I. Inc.

Late in June, High Tide

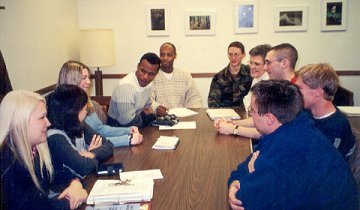

Software (HTS) of Focus Group Research

When should you consider

using focus group research? Like

surveys, market experiments, and test markets, focus group research is just

one of the many techniques that fall under the larger category of “Marketing

Research.” First and foremost, a focus

group is a “proof of concept” technique.

It is by definition qualitative research. There are few, if any, statistics emanating

from this effort. It is most usefully

employed in the middle of product (or service) development. The product must be fairly well along such

that the group can get a good idea of what it looks like, what it does, and

how he might use it. The group will be

the first real “users” to look at this new entity. What you want to gain from focus group

research is their reaction to the new offering. In the paragraphs that

follow we are going to outline the steps of a typical client engagement

involving focus group research. As an

example we have drawn on an actual project we did for a major computer

manufacturer. The first thing that we

need to establish is the “research objective.” That is, what question is the research

going to answer.

The client was thinking

of packaging up some professional services to be sold and delivered by

partners who are Value Added Resellers (VARs). The client wanted to know how this would be

received by the VARs. We proposed

using focus groups, made up of VARs, to address this question. Our research objective was to find out if

the VARs would enthusiastically resell and deliver the services packaged by

our client. By the end of our

engagement we needed to have a yes or no answer. Once we establish the

objective we need to concern ourselves with the logistics of running the

sessions. Often you need geographic

dispersion. This was the case in our

study as we ran four groups in three American cities and one Canadian

location. It is very important that

the group be composed of people who look like the market in general. Because focus groups are between 10 and 20

people you must recruit the attendees with skill. We had representation from big VARs and

small. We had people with both wide

and narrow product focus. We had

attendees who sold our client’s products exclusively and those who handled

additional competitive lines. It was

deemed important to feed the attendees, pay them for their time, and record

each session on video. Although it is not

mandatory, we believe that every focus group should have a “model

product.” In our case it was a model

service. This is something concrete

that you can put down on the table so that the attendees can get a real feel

for what the finished offering will look like. Since we were testing a service, the

moderator (the person running the focus group) took five minutes to describe

our model service. Our client was

proposing to offer an installation service for a very large computer storage

product. The service was created by

our client, but sold and performed by the VARs. So we have our attendees

coming, we know what we need to find out, and we have an example to put

before them. What will keep the two

hours flowing smoothly? The answer is

the Moderator’s Guide Book. While

months of preparation meant that we really knew our subject, by documenting

our work we assured our client and ourselves that each of the four sessions

would be very similar in organization.

The major component of the book is the session outline. Blocks of time are allotted to such things

as introduction, model product, and moderator questions. The role of the moderator is mostly to ask

probing questions. He is not to give

his opinion. There are two types of

questions. First are the “timeline”

questions. These are the questions

that will always be asked at a certain point in the session. For example “Are your customers asking for

installation services you do not currently provide?” Beyond the timeline questions there are

another set of questions which may be used.

These are called “shepherding” questions. If the discussion is wandering down an

unproductive path, the moderator needs to bring the flock back on track. The guide book has many of these questions

which is hoped will not have to be used.

An example of a shepherding question is: “Could an installation

service add significantly to your profits?”

Now you are all set with

your guide book in hand to run the focus groups. When they are all complete you take the

video tapes and transcribe each session.

Everything that an attendee says is coded with a number. Because the sessions are on tape, most of

the time you can coordinate the comment to a person and a company. This provides the major input to the final

report. Some would not do anything in

the final report save a general comment as to a sense of the sessions thus

leaving it up to the client to draw his own conclusions. This is not the way we do it. First, we explain in

general how we met the research objective.

In our example study the VARs would resell and deliver the kind of

services our client was developing.

Second, we

defended each and every conclusion with the coded comments transcribed

directly from the tapes. Thus, we did

not state our conclusions as assertions, but proved them one by one. Finally, we added new insight that came out

of the focus group serendipitously.

These were concepts that the client had not foreseen. In our work we found that the VARs would

not only like to resell the packaged services of our client, but the packaged

services of other VARs! This was news

to our client as our client believed that the VARs looked at other VARs in

the room as competitors. This was

clearly not the case. For additional information:

bob@s-i-inc.com

Or send USPS mail to: |